Tony Fadell cleans out his garage – TechCrunch

“Anyone want to see what I unearthed when I cleaned out my garage and found photos of everything I’ve ever made?” Tony Fadell tweeted in mid-April. It was a rhetorical question. Anyone with a passing interest in the last two decades of consumer hardware would jump at the opportunity to see what the man behind the iPod, iPhone and Nest Thermostat had stashed away in those giant Home Depot boxes.

The literal garage cleaning preceded the metaphorical variety, with this week’s publication of “Build: An Unorthodox Guide to Making Things Worth Making.” The book charts Fadell’s path to some of consumer electronics’ most iconic hardware designs. It’s concerned with, above all, the “why” of product design. It’s a word he uses 50+ times over the course of our 30-minute conversation.

We reached out to Fadell’s team following the tweet, asking if we might be able to get in on the garage sale. They happily complied, sending along a dozen images that provide a rough guide of the product designer’s career, from the early days through his time at Nest.

The story starts in the early 90s, when he joined General Magic, fresh out of the University of Michigan. The Apple spinoff’s trials and tribulations were highlighted in a 2018 documentary of the same name that features Fadell among the talking heads.

“The reason you should care about the story of General Magic is that it involves something fundamental, and that is: Failure isn’t the end, failure is actually the beginning,” the company’s spokesperson says at the end of the trailer and the top of the film.

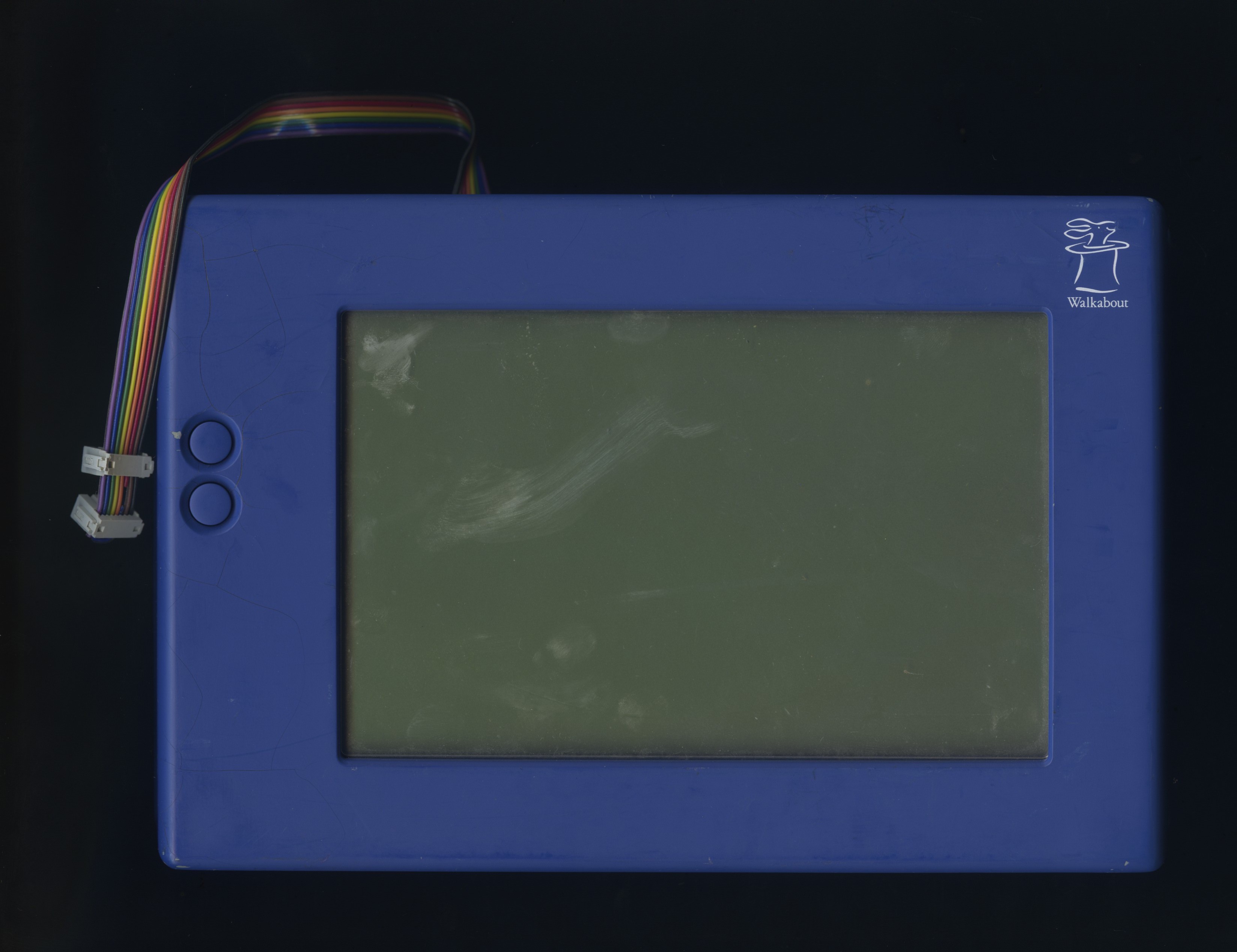

Image Credits: Courtesy of Tony Fadell

Above is a prototype of one of General Magic’s spectacular and inspiring failures, the Walkabout.

“All we had was big boards and a big LCD,” Fadell explains. “That was something I got to work on, when I was there. You look at the technology of the day, and we were solving problems for ourselves. We weren’t solving problems that people had. Very few people had email in 1991, 92. Nobody was downloading apps — it wasn’t fast enough to contemplate. Even mobile/wireless communications. There was ticketing. You could book travel. There wasn’t even a web yet. There was no Wi-Fi, no mobile phones, no data networks.”

Timing, as they say, is everything. Fifteen years before the iPhone arrived, it’s safe to say that the Walkabout was a bit early to the party. Operating largely in secret, the company sought to resolve internet pain points a decade before they were on most people’s radar.

“I think a lot of people were dreaming this stuff up,” Fadell explains. “We were one of the first incarnations of actually putting this stuff together well before the technology — or, more importantly, society — was ready for it. They didn’t know they were going to have these problems because they didn’t have them until they showed up 15 years later. When you’re designing in that kind of vacuum, this is what comes out. It was amazing. Everyone’s like, ‘this is so cool, but why do I need it?’”

This brings us to the “why.” Or the “why, why, why,” as Fadell excitedly puts it. It’s the three-word question any product designer must answer before getting to the “how, how, how” — as tempting as it might be to tackle that second part first. It’s one of those concepts that’s obvious in hindsight, but difficult in the thick of things, when you’re surround by a group of smart people looking to make cool things.

Fadell says the seemingly obvious notion came into stark relief during a round of the word game, Scramble.

“That’s what everyone was using it for,” he says. “There was almost nothing else people were using it for, day in and day out. And then you start scratching your head, going, ‘how much does this cost? Who’s going to buy it? What’s it for.’ And that’s when you start realizing you spent three or four years of your life on it, and what could it be used for? We have this general capability. What could it be used for?”

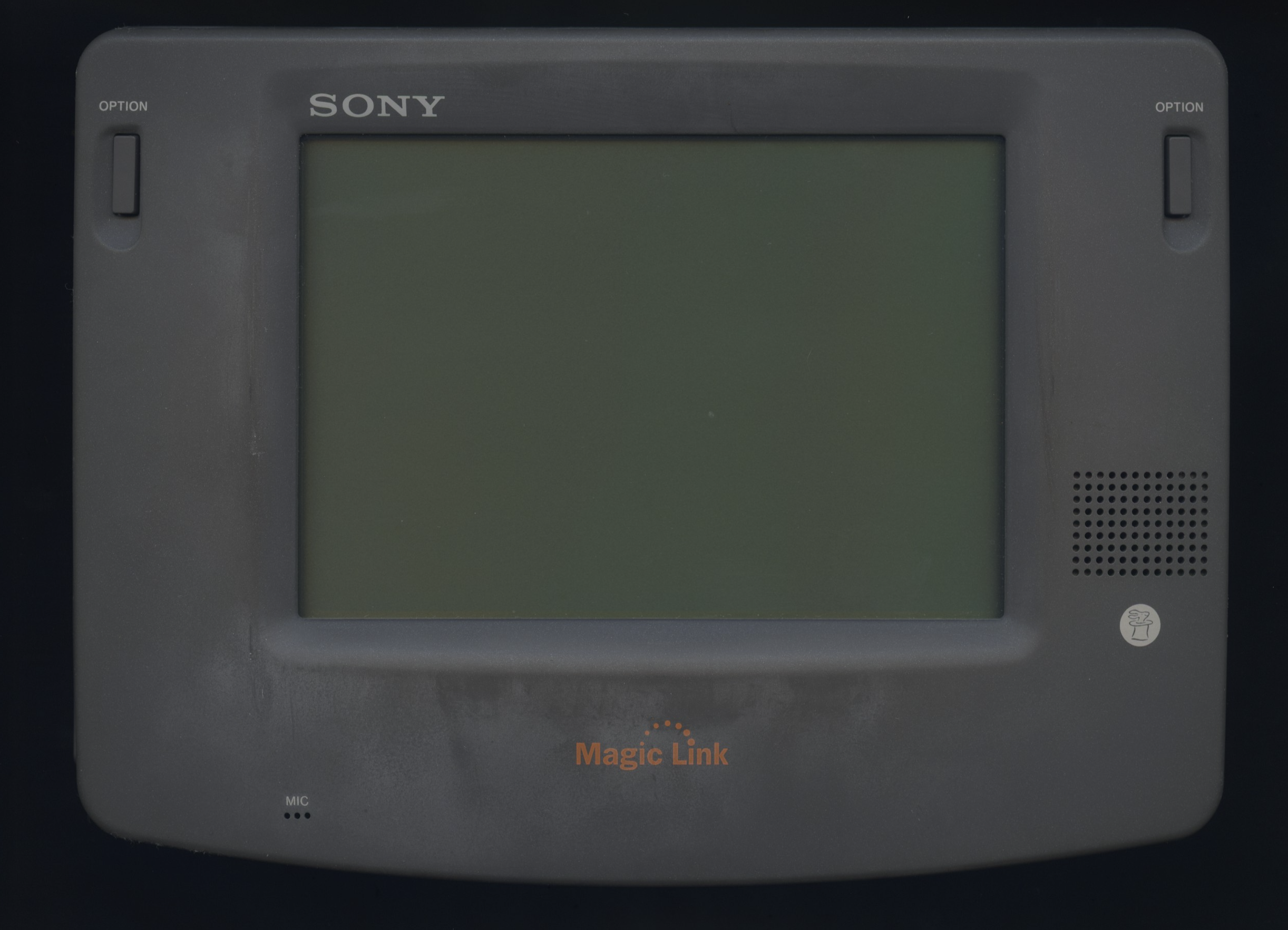

Image Credits: Courtesy of Tony Fadell

The research would eventual give rise to an early generation of PDAs like Sony’s Magic Link and Philips’ Velo. “I was reading about how to write a business plan and presentation, and it was like, ‘what’s the why?’” Fadell explains. “The why? I swear, it took four or five days to start to even think in those terms of why, why, why? Because that was my whole life, thinking what, what, what?”

After a stint at Philips, Fadell once again found himself ahead of the adoption curve — albeit significantly less this time. Attempts to bring the Fuse music player to market were hamstrung, in part, by funding that had dried up as a result of the recent dot-com bubble burst. Two years later, however, he found himself realizing those dreams on a far larger stage at Apple, with the development of the first iPod.

Three years later, the company began working in earnest on a smartphone. After the Motorola ROKR E1 proved a major non-starter, the company shifted focus to in-house design, borrowing heavily from iPod learnings and designs.

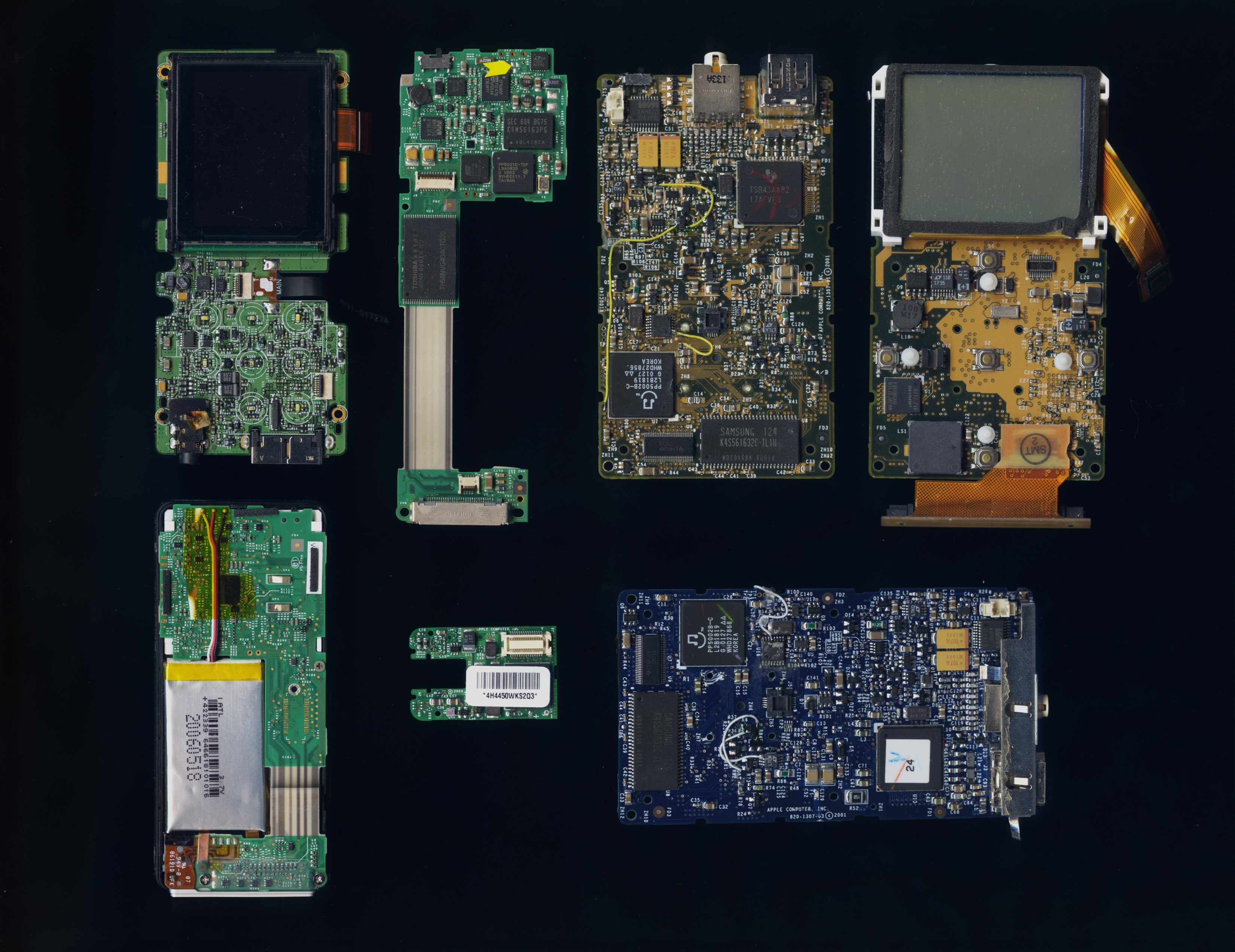

Image Credits: Courtesy of Tony Fadell

“That is a prototype that a third-party manufacture sent to me, saying, ‘We’re capable. Look at this cool thing we did,’ and ‘I think you should pick us because we can help you with this iPod Phone concept,’” Fadell says of the above shot. “The top and the bottom have a swivel, so you can have either the number pad or click wheel or camera. It was really cool that people were thinking about it. It wasn’t half bad! It doesn’t work for a lot of reasons, but it’s not bad thinking.”

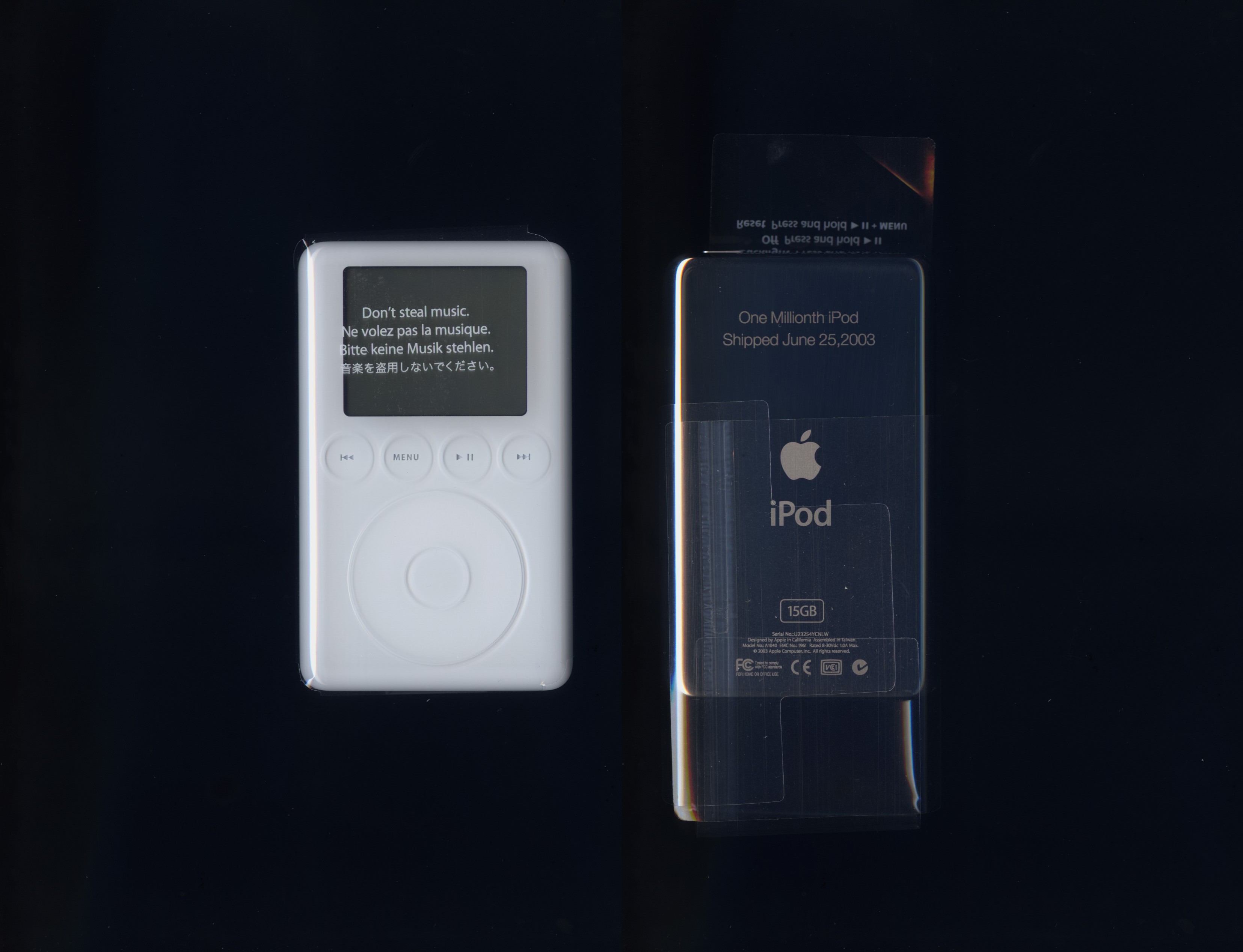

Image Credits: Courtesy of Tony Fadell

Initial work on the iPhone started in a similar place.

“We did iPod Plus Phone,” says Fadell “You took the headset, which had a microphone on it and the one ear thing. You could use the Click Wheel to select numbers and names, or you could dial with it, like a rotary phone, which was the ultimate death of it. You couldn’t enter anything, because there’s no textual input. But it was an iPod Classic with a phone in it. Walk it back from the third-party prototype, and we were there, too.”

Image Credits: Courtesy of Tony Fadell

Fadell says it was Steve Jobs who pushed the team on marrying the iPod’s success with the secretive phone project. The company had, after all, developed something iconic and inutive with the iPod click wheel, so why would it go and do something as foolhardy as cannibalizing the input device with a touchscreen?

Image Credits: Courtesy of Tony Fadell

“[Jobs] had very clear views on things — until they weren’t clear,” he says. “Or it became very clear that they wouldn’t work. He pushed us very hard on making the iPod Plus Phone work. We worked weeks and weeks to figure out how to do input with the click wheel. We couldn’t get it, and after the whole team was convinced we couldn’t do it, he was like, ‘keep trying!’ At some point we all said, ‘no, it isn’t going to work.’”

The ”iPod Plus Phone” was one of three concepts that eventually resulted in the first iPhone.

Image Credits: Courtesy of Tony Fadell

“There was the fullscreen iPod, because we had video at the time,” he explains. “We had the screen plus the wheel, so let’s make the wheel virtual on the screen and have a single touch display. The third thing, from a hardware perspective, was a touchscreen Mac, which was multi-touch. That was being worked on in another part of the company. A company called FingerWorks was purchased by Apple. A guy named Steve Hotelling came up with the idea of a multi-touch screen, but it was the size of a ping-pong table. It had a projector in the middle of it, and all that stuff. We had to go and cram that all down and combine the cell phone functionality from the iPod Plus Phone and the screen capability and the virtual interface together.”

Fadell’s Jobs stories paint a familiar vision of a visionary whose perfectionism could often result in long hours in Cupertino. We made a decision early on that we weren’t going to have glass on [the iPhone],” he says. “And after it was revealed to the world, Steve was like, ‘we gotta have glass on it.’ You have all of the mechanical and rigidity issues that you have to design for. If you design for plastic, instead of glass, it’s a very different experience. In the span of two months, we had to move from plastic to glass and reengineer everything, including the antennae to get it right.”

Image Credits: Courtesy of Tony Fadell

In 2008, The Wall Street Journal broke the news that Fadell was leaving the company. “People familiar with the matter said Mr. Fadell planned to take time off after leaving the company though he may still keep a role at Apple as a consultant,” the paper wrote. Apple, unsurprisingly, refused to comment on “rumors and speculation.”

Fadell would once again launch his own company. This time out, however, it fared far better. Founded in 2010 with fellow Apple ex-pat, Matt Rogers, Nest would be acquired by Google four years later, serving as the foundation of the company’s smart home offerings. It was a big jump from the world of music players and phones to thermostats and smoke alarms.

You go from more or less entertainment to this thing that’s highly functional and has zero design around it,” Fadell says of the Nest Thermostat. “You need it to control the temperature — but why you really need it is to control the money you spend. That’s where we had to change the narrative, and that’s why the storytelling was so critical at Nest. One was to make it look cool to draw people in. And two, why do you need to pay five to 10 times more for this thing? It’s technology in service of something really important. But nobody cared.”

When he’s not promoting a book or cleaning his garage, Fadell serves as the principal at Future Shape, helping startups bring their visions to life.

“Many companies that come to me with hardware, I ask why they need it,” he says. “I try to get rid of the hardware, if I can, because it’s too much friction. I see so many people getting distracted because it’s a cool thing. What we do is make sure the hardware is absolutely necessary — that it’s in service of the planet, societies or health. We care about funding things that are going to help fix those things.”

“Build: An Unorthodox Guide to Making Things Worth Making” is available now from HarperCollins Publishers.

Recent Comments